In the world of architecture, some names don’t just design buildings — they redefine what buildings can be. Zaha Hadid, often called the “Queen of the Curve,” was one such visionary. Known for her fluid, gravity-defying forms, Hadid transcended traditional architecture, blending mathematics, abstraction, and technology into futuristic masterpieces. Her work wasn't just about creating usable spaces. It was about reimagining how architecture feels, moves, and transforms within the urban landscape. This is why she is often remembered not just as a great architect, but as a radical thinker who moved beyond function. Who Was Zaha Hadid? Born in Baghdad, Iraq, in 1950, Zaha Hadid studied mathematics before pursuing architecture at the Architectural Association in London. She was mentored by renowned figures like Rem Koolhaas and Elia Zenghelis, where her early designs already hinted at her boundary-pushing vision. In 1979, she founded Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA) in London. Initially known more for her provocative drawings than built work, Hadid spent nearly two decades as a "paper architect" — until the world finally caught up with her vision. Her first major commission, the Vitra Fire Station in Germany (1993), set the tone for what was to come: dynamic geometries, fragmented spaces, and bold lines that defied conventional logic. The Early Journey: From Baghdad to the Architectural World Stage Zaha Hadid was raised in a progressive and intellectual household. Her father, Mohammed Hadid, was a politician and economist, and her upbringing exposed her to a rich blend of modernism and Middle Eastern …

Zaha Hadid: Fluid Forms Beyond Function

In the world of architecture, some names don’t just design buildings — they redefine what buildings can be. Zaha Hadid, often called the “Queen of the Curve,” was one such visionary. Known for her fluid, gravity-defying forms, Hadid transcended traditional architecture, blending mathematics, abstraction, and technology into futuristic masterpieces.

Her work wasn’t just about creating usable spaces. It was about reimagining how architecture feels, moves, and transforms within the urban landscape. This is why she is often remembered not just as a great architect, but as a radical thinker who moved beyond function.

Who Was Zaha Hadid?

Born in Baghdad, Iraq, in 1950, Zaha Hadid studied mathematics before pursuing architecture at the Architectural Association in London. She was mentored by renowned figures like Rem Koolhaas and Elia Zenghelis, where her early designs already hinted at her boundary-pushing vision. In 1979, she founded Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA) in London. Initially known more for her provocative drawings than built work, Hadid spent nearly two decades as a “paper architect” — until the world finally caught up with her vision.

Her first major commission, the Vitra Fire Station in Germany (1993), set the tone for what was to come: dynamic geometries, fragmented spaces, and bold lines that defied conventional logic.

The Early Journey: From Baghdad to the Architectural World Stage

Zaha Hadid was raised in a progressive and intellectual household. Her father, Mohammed Hadid, was a politician and economist, and her upbringing exposed her to a rich blend of modernism and Middle Eastern culture. She pursued mathematics at the American University of Beirut before moving to London in the 1970s to study at the Architectural Association (AA) School of Architecture — one of the most experimental institutions of its time.

It was at AA that Hadid studied under Rem Koolhaas and other influential architects, who helped sharpen her bold vision. Even in her student years, she stood out for her abstract, almost unbuildable designs, inspired by Russian Constructivism, Suprematism, and avant-garde art.

Breaking Through the Glass Ceiling

Hadid established her own firm, Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA) in 1980. However, for many years, her designs were considered too radical to build. Early works like “The Peak” in Hong Kong (1983) and the Cardiff Bay Opera House (1994) remained unbuilt despite critical acclaim. These “paper architecture” projects showcased her bold vision but also highlighted how hard it was for a woman of color to break into a conservative, male-dominated field.

Her persistence paid off. In 1993, her first major built project, the Vitra Fire Station in Germany, showcased her geometric and deconstructivist style. Angular, raw, and visually striking, it marked the start of an architectural revolution.

Fluid Forms: The Signature Style

Zaha Hadid’s architectural language is often described as:

- Fluid

- Non-linear

- Organic

- Parametric

- Sculptural

Where traditional architecture clings to right angles and repetitive grids, Hadid’s work flows like a landscape. Her structures often appear as if they’re in motion—even when frozen in concrete or steel.

🌀 “There are 360 degrees, so why stick to one?” — Zaha Hadid

This ideology wasn’t just aesthetic—it was philosophical. She believed architecture should reflect complexity, diversity, and modern life’s fluid nature.

Beyond Function: Reimagining Space

While form-follows-function is a classic design mantra, Hadid reversed the narrative. Her work introduced a new spatial typology—one that didn’t just house activities but created experiences.

Rather than being confined by structural necessity, she used:

- Advanced algorithms and parametric modeling

- Digital fabrication

- New material innovations

This liberated architecture from the constraints of rigid function, allowing art and engineering to co-exist in built environments.

Iconic Projects That Embody Her Philosophy

1. Heydar Aliyev Center, Baku (2012)

One of her most celebrated works, this cultural center in Azerbaijan feels like silk caught in the wind. There are no sharp edges. Instead, the structure ripples, curves, and swells—a metaphor for openness and movement.

2. MAXXI Museum, Rome (2010)

The Museum of 21st Century Arts features layered, overlapping spaces, walkways, and voids. The concrete flows like ribbons, guiding visitors through light and shadow.

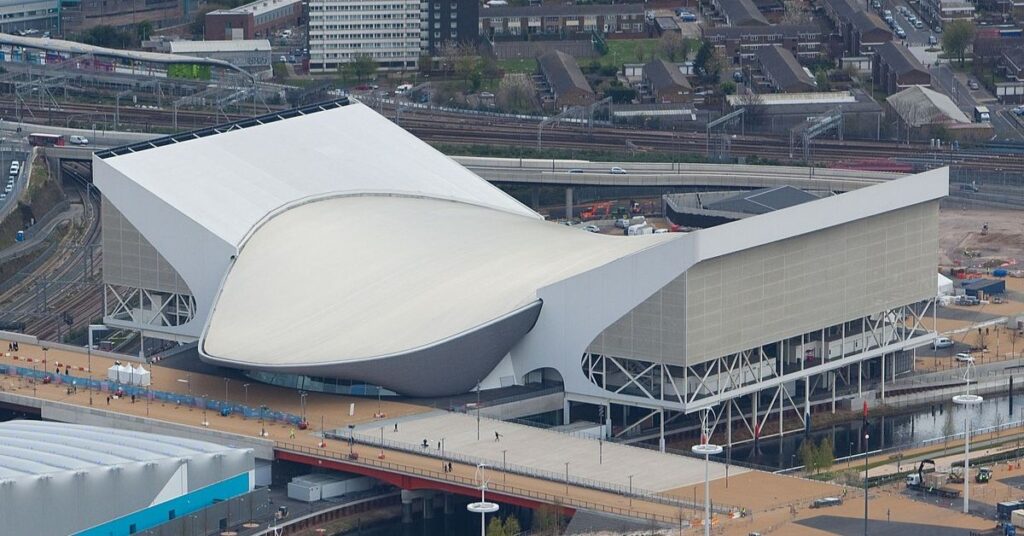

3. London Aquatics Centre (2011)

Built for the 2012 Olympics, this design mimics the undulating movement of water, with its wave-like roof and organically flowing interior.

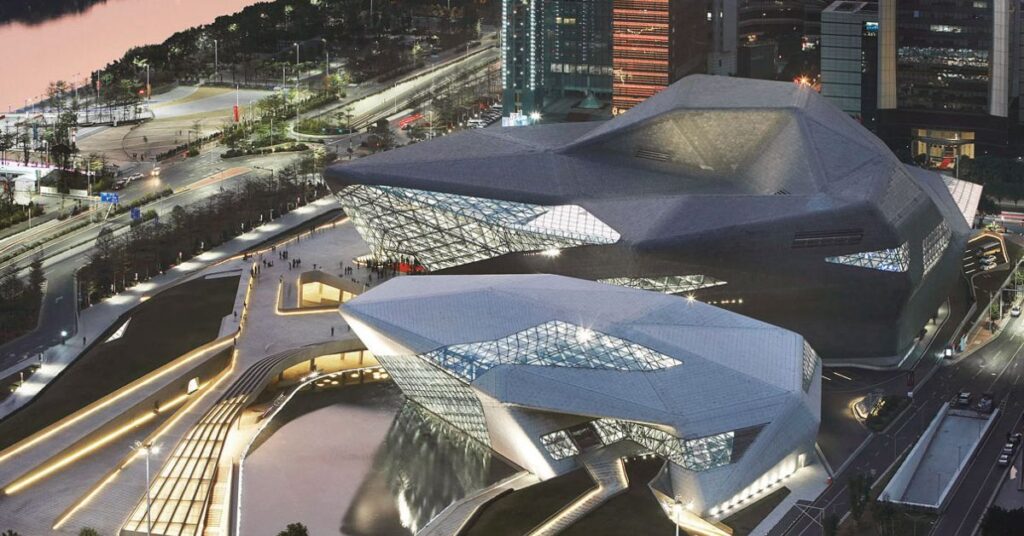

4. Guangzhou Opera House, China (2010)

Inspired by river pebbles, this asymmetrical building integrates seamlessly with the surrounding urban landscape. Its fragmented geometry reflects Hadid’s belief in fluid integration between architecture and nature.

Technology as a Design Partner

Hadid was one of the first architects to embrace digital technology as a core design tool. Through:

- Parametric design (especially with the help of Patrik Schumacher)

- 3D modeling

- Generative scripting

She unlocked the freedom to create previously unbuildable forms. Algorithmic logic allowed her to manipulate space in ways traditional drafting never could.

Legacy and Impact

Zaha Hadid passed away in 2016, but her legacy lives on—not only in the iconic buildings she left behind but in the paradigm shift she created. Her firm, ZHA, continues to push the envelope under the leadership of Patrik Schumacher.

Her influence can be seen in:

- The rise of parametric design in global architecture

- More female voices in a historically male-dominated field

- The acceptance of architecture as experiential art

Criticism and Controversy

Despite the acclaim, her work was not without criticism:

- Some called it excessive or impractical

- Others argued that form overtook function

- Labor and political issues around mega-projects (e.g., Al Wakrah Stadium in Qatar) raised ethical questions

But even critics could not deny: Zaha Hadid moved architecture forward. She made it bolder, riskier, and more expressive.

Zaha Hadid’s Vision in 2025 and Beyond

Hadid envisioned a world where buildings communicate movement, emotion, and context. In 2025, as AI, sustainability, and digital fabrication evolve, her influence is stronger than ever:

- Sustainable parametric forms that reduce waste

- Algorithm-driven design echoing her early experimentation

- Cultural architecture that breaks borders and conventions

Her work remains a blueprint for a future that blurs the lines between art, code, and culture.

Conclusion: More Than Buildings

Zaha Hadid didn’t just design structures—she sculpted experiences, challenged norms, and expanded the vocabulary of contemporary architecture. To design “fluid forms beyond function” is to question, push, and imagine beyond what we think a building should be.

In the echoes of her sweeping curves and limitless geometries, we hear the future calling.